I spoke tonight at the Brisbane WordPress meetup about Git basics, moving up to more advanced Git usage, and using Git with WordPress. A recording with audio is coming soon, but in the meantime, here are my slides.

I’d love any feedback on this!

The personal weblog of Ryan McCue.

I spoke tonight at the Brisbane WordPress meetup about Git basics, moving up to more advanced Git usage, and using Git with WordPress. A recording with audio is coming soon, but in the meantime, here are my slides.

I’d love any feedback on this!

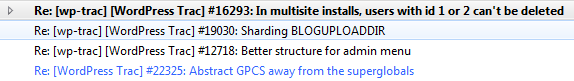

For those who follow me on Twitter, you’d know that I recently attended the WordPress Community Summit. (If you’re expecting a long blog post on the summit, you must be new to my blog. 😉 ) One of the suggestions that came up was to subscribe to the WP-Trac mailing list. This list gets a copy of every comment and change (except attachments) on Trac tickets, and is the a great way to follow activity on WordPress, since you get to see every issue change that happens.

However, following this activity comes with a giant downside: there is a lot of activity on Trac, so it can be hard to keep track of all the things going on; for this reason, it’s commonly called drinking from the firehose1 CC-ing yourself on a ticket (or getting auto-CC’d when you comment) is a great way of getting informed of any changes to it, but if you’re drinking from the firehose, this becomes fairly useless: either you get two copies of each change, or you only get one and CC-ing does nothing.

Thankfully, with a little Thunderbird magic, I’ve come up with an optimal solution: CC’d emails come through to my main email address, while the mailing list is sent through to my firehose email account. I then set up a Thunderbird filter to move the message from my main email to the firehose account, and apply a “CC’d” label to it. Thunderbird merges the messages, since they have the same message ID, then applies the label to the merged message. I can check at a glance and see what’s important to me, while still retaining the ability to follow the project as a whole.

For those of you who want to get involved more in WordPress, I’d definitely recommend this. Already I’ve noticed more stuff that interests me, and it’s fairly minimal effort to go through the messages.2

Anyone who has seen me talk in the #wordpress-dev IRC room will know that I’m

not a huge fan of WP_Error. However, for some insane reason, some people are.

I figured it’s probably time to explain why WP_Error sucks, and what we can do

about it.

Back in the days of WordPress 2.0, errors were handled by returning false from

WordPress functions, or occasionally error strings. For 2.1, it was decided

to change this to returning an error object instead. This error object gave the

ability to indicate an error had occurred, but still include information with

the error that could be used programmatically, or as a user-friendly message.

Given the context of its conception, WP_Error was a great idea; it gave the

easy ability to pass data regarding errors around while still noting that it

was an error, rather than actual data.

Currently, most WordPress functions return a WP_Error object if something goes

wrong. Based on what I wrote just before, this might seem like an awesome idea.

However, imagine what happens if I have a helper function:

/**

* Retrieve and decode JSON data from a URL

*/

function rmccue_my_http_helper($url) {

$response = wp_remote_get($url);

if (is_wp_error($response)) {

return $response;

}

return json_decode($response['body']);

}

This might seem fine, but note that we have to handle WP_Error differently here.

Errors give no useful information to this function, so we could just return

false. However, this deprives the caller function of the ability to find out

about the error.

For an example of when this becomes unwieldy, let’s look at what happens when

the above function gets used:

/**

* Get current message from API

*/

function rmccue_get_api_msg() {

$data = rmccue_my_http_helper('http://api.example.com/');

if (is_wp_error($data)) {

return $data;

}

return $data['apidata']['messages']['latest'];

}

/**

* Output result to header

*/

function rmccue_output_message() {

$message = rmccue_get_api_msg();

if (is_wp_error($message)) {

echo $message->get_error_message();

}

else {

echo $message;

}

}

Note that we now have three places where we’re checking if we got an error

back, but only one place where that check is actually useful (i.e. when we

output it).

Even worse than this is when developers forget to check for errors (I’ll admit,

I’ve been guilty of this many times). Suddenly, they’re trying to use a

WP_Error object as an array or an integer, and PHP will fail, or worse, give

garbage output.

As anyone who has worked with WordPress knows, WordPress supported PHP 4 for a

long time, even after many other projects had switched. The advantage of this

was supporting significantly more hosts, with most PHP 5-only features either

not being needed or being easy to reimplement.

One of the new features added to PHP in PHP 5 was exception handling. For those

who aren’t aware of it, exception handling is a way to indicate an error and

have it handled at an appropriate place without having to check values

constantly. This might sound familiar to you: isn’t this what WP_Error was

intended to solve?

The answer is yes, but not quite. WP_Error is essentially the poor man’s

exception. Unlike WP_Error, the basic idea of exceptions is that you only

worry about errors where they actually matter and lower-level functions can

forget about needing them. Exceptions continue up the call stack until they’ve

been caught, when they can then be handled as necessary.

This might seem a bit confusing, so here’s what our previous example would look

like if we used exceptions instead (assuming wp_remote_get() threw a

WP_Exception exception):

/**

* Retrieve and decode JSON data from a URL

*/

function rmccue_my_http_helper($url) {

$response = wp_remote_get($url);

return json_decode($response['body']);

}

/**

* Get current message from API

*/

function rmccue_get_api_msg() {

$data = rmccue_my_http_helper('http://api.example.com/');

return $data['apidata']['messages']['latest'];

}

/**

* Output result to header

*/

function rmccue_output_message() {

try {

$message = rmccue_get_api_msg();

echo $message;

}

catch (WP_Exception $exception) {

echo $exception->get_error_message();

}

}

See the difference? Instead of having to check at every level for exceptions, we

can now just let the exception pass up to somewhere that matters.

How does this work? In this case: if wp_remote_get() throws an exception, this

is passed up to rmccue_my_http_helper(). There’s no try ... catch in this

function, so we continue up the callstack, through rmccue_get_api_msg() until

we hit the try ... catch in rmccue_output_message(). Here, we catch the

exception and handle it as appropriate.

Exceptions also provide valuable context for developers. Rather than having to

check all the places where the error could have occurred, every exception

includes a traceback; that is, the entire callstack up until when the exception

was thrown. This gives you an easy way to see where an error occurred and makes

debugging much easier.

Although WordPress doesn’t use exceptions internally, you can already start

using them. For example, Renku uses them internally to save on a lot of

code.

The basic concept of using exceptions in your code is simple: whenever you get

a WP_Error object, convert it to an exception. In our above example, this

would mean handling it in rmccue_my_http_helper() and

rmccue_output_message(), but we’d no longer have to handle it inbetween.

Here’s what the above would look like:

/**

* Retrieve and decode JSON data from a URL

*/

function rmccue_my_http_helper($url) {

$response = wp_remote_get($url);

if (is_wp_error($response)) {

throw new Exception($response->get_error_message(), $response->get_error_code())

}

return json_decode($response['body']);

}

Here, we convert the WP_Error to an exception as soon as possible, allowing us

to skip most of the extra handling in our code.

Unfortunately, exceptions don’t appear to be getting into core any time soon.

Some of the core developers are very against exceptions (for reasons I can’t

completely comprehend). One of the arguments made against using exceptions in

core was the possibility of confusing theme developers. I’d actually make the

counter-argument that WP_Error is more confusing to theme developers. Having

to check at every possible stage if a result is_wp_error() is much more

confusing and is not something that theme developers are necessarily going to

remember.

Another of the issues I’ve heard raised is that of the fatal nature of

exceptions. Any exceptions that haven’t been caught by the time they get to the

top-level are handled by a default exception handler, or failing that, cause a

fatal error. The solution for WordPress is easy: firstly, add a default

exception handler that uses wp_die(), much like the existing handling for

fatal errors; secondly, add a try ... catch inside

do_action()/apply_filters(). Most plugins run the majority of their code

inside actions/filters, so this would ensure that any exceptions would only

cause that specific callback to fail. This would keep WordPress running with

minimal interruptions to the existing workflow.

The only issue that I can see is one of backwards compatibility. The best way to

deal with that would be to announce that exceptions will be used in two releases

time (for example), and to encourage developers to switch to it. WP_Error

could immediately be changed to extend WP_Exception (which would in turn

extend Exception). This would give the ability for proactive plugin developers

to switch easily. For example, our HTTP helper function:

/**

* Retrieve and decode JSON data from a URL

*/

function rmccue_my_http_helper($url) {

$response = wp_remote_get($url);

if (is_wp_error($response)) {

if (class_exists('WP_Exception') && $response instanceof WP_Exception) {

throw $response;

}

else {

throw new Exception($response->get_error_message(), $response->get_error_code())

}

}

return json_decode($response['body']);

}

This would give complete forward and backward compatibility for these plugins

and enable a smooth transition to exceptions.

So, what are you waiting for? Get out there and use exceptions!

As part of my most recent project (which you’ll be hearing more about very soon), I’ve been working with WP e-Commerce and having a tonne of fun dealing with all the bits and pieces. In general, it has been quite handy, since it has meant I don’t have to deal with implementing all the payment handling and such. However, it does have its issues, including a fairly horrible API.

WPEC is also quite a bit inefficient, due in part to its customisability. However, it’s definitely nothing insurmountable with a bit of code and some clever tricks.

Note: I’ll be using code from 4.0-dev in examples, but it should all be the same for the latest stable version as well.

So, with all of that out of the way, let’s get started. First step in optimising anything in WordPress is to turn WP_DEBUG on. We’ll also want to turn SAVEQUERIES on so that we can see what exactly is getting queried. The Debug Bar plugin will also help to view the results of these.

To start off with, here’s the MySQL queries that were generated by WPEC for me on a non-WPEC page:

SELECT option_value FROM wpstore_options WHERE option_name = '_transient_timeout_wpsc_theme_path' LIMIT 1 SELECT option_value FROM wpstore_options WHERE option_name = '_transient_wpsc_theme_path' LIMIT 1 SELECT option_value FROM wpstore_options WHERE option_name = 'wpsc_replace_page_title' LIMIT 1 SELECT option_value FROM wpstore_options WHERE option_name = 'wpsc_hide_featured_products' LIMIT 1 SELECT option_value FROM wpstore_options WHERE option_name = 'base_zipcode' LIMIT 1 SELECT option_value FROM wpstore_options WHERE option_name = 'wpsc_ups_settings' LIMIT 1 SELECT post_name FROM `wpstore_posts` WHERE `post_content` LIKE '%[productspage]%' AND `post_type` = 'page' LIMIT 1 SELECT post_name FROM `wpstore_posts` WHERE `post_content` LIKE '%[shoppingcart]%' AND `post_type` = 'page' LIMIT 1 SELECT post_name FROM `wpstore_posts` WHERE `post_content` LIKE '%[transactionresults]%' AND `post_type` = 'page' LIMIT 1 SELECT post_name FROM `wpstore_posts` WHERE `post_content` LIKE '%[userlog]%' AND `post_type` = 'page' LIMIT 1 SELECT option_value FROM wpstore_options WHERE option_name = '_transient_timeout_wpsc_url_wpsc-default.css' LIMIT 1 SELECT option_value FROM wpstore_options WHERE option_name = '_transient_wpsc_url_wpsc-default.css' LIMIT 1 SELECT option_value FROM wpstore_options WHERE option_name = 'google_server_type' LIMIT 1 SELECT option_value FROM wpstore_options WHERE option_name = 'google_cur' LIMIT 1

That’s 14 queries for essentially nothing! Even worse are the four fulltext queries to find those shortcodes. Surely we can do better.

So, let’s start cutting pieces out. The first part that concerned me was the two google_ queries, as I’m not using Checkout. As it turns out, the Google Checkout plugin does all sorts of stuff even if it’s not loaded. This is not something we want. However, this is easy to fix. WPEC loads everything in the wpsc-merchants/ directory, but no other code relies on these merchants, so simply remove the ones you don’t need. We’re using Brent Shepherd’s PayPal Digital Goods payment gateway (which hopefully will make it into WPEC 4.0). This gateway uses the new 4.0 merchant gateway classes, so we don’t actually need anything in wpsc-merchants/. Before you remove all the files though, note that a blank directory will cause errors, so leave testmode.merchant.php to avoid this.

Right, we’re now down to 12 queries. Next job, cutting out the shipping information. Both base_zipcode and wpsc_ups_settings are being loaded, despite no shipping handlers being activated. As our store is purely virtual goods, we don’t need any of the shipping items, so we’ll do as before and remove them all. Be wary of the blank directory issue though, and leave at least one file in there (I chose flatrate.php).

OK, 10 queries! We’re making great progress. Next step is wpsc_replace_page_title and wpsc_hide_featured_products. Go into the presentation tab of your settings and resave, and this should save these to the database and set the autoload property, causing them to be loaded in the initial WordPress settings query. However, I noticed this was not happening on our server (I suspect that if they are set to off, they simply aren’t being saved), so I hardcoded them in the theme:

// pre_option_$x doesn't like false, so return 0 instead

add_filter('pre_option_wpsc_replace_page_title', '__return_zero');

add_filter('pre_option_wpsc_hide_featured_products', '__return_zero');

Of course, if you want to enable them, you should use '__return_true' here instead, however the settings page should work for this.

By now, we should be down to the following 8 queries:

SELECT option_value FROM wpstore_options WHERE option_name = '_transient_timeout_wpsc_theme_path' LIMIT 1 SELECT option_value FROM wpstore_options WHERE option_name = '_transient_wpsc_theme_path' LIMIT 1 SELECT post_name FROM `wpstore_posts` WHERE `post_content` LIKE '%[productspage]%' AND `post_type` = 'page' LIMIT 1 SELECT post_name FROM `wpstore_posts` WHERE `post_content` LIKE '%[shoppingcart]%' AND `post_type` = 'page' LIMIT 1 SELECT post_name FROM `wpstore_posts` WHERE `post_content` LIKE '%[transactionresults]%' AND `post_type` = 'page' LIMIT 1 SELECT post_name FROM `wpstore_posts` WHERE `post_content` LIKE '%[userlog]%' AND `post_type` = 'page' LIMIT 1 SELECT option_value FROM wpstore_options WHERE option_name = '_transient_timeout_wpsc_url_wpsc-default.css' LIMIT 1 SELECT option_value FROM wpstore_options WHERE option_name = '_transient_wpsc_url_wpsc-default.css' LIMIT 1

So, first, let’s look at those transients. These transients work by caching where the WPEC theme files exist, to avoid having to check the stylesheet directory, then the template directory, then the default WPEC directory. There are two options to changing this: you can either head into your MySQL database and set the autoload value for these options to yes, or simply hardcode it. Personally, I know where these files are always going to live, so I went with hardcoding:

add_filter('pre_transient_wpsc_theme_path', array(__CLASS__, 'hardcode_wpsc_theme_path'));

add_filter('pre_transient_wpsc_url_wpsc-default.css', array(__CLASS__, 'hardcode_wpsc_theme_url'));

public function rm_hardcode_wpsc_theme_path($value) {

return WPSC_CORE_THEME_PATH;

}

public function rm_hardcode_wpsc_theme_url($value) {

return get_stylesheet_directory_uri() . '/wpsc-default.css';

}

We’ve now hardcoded most things and we’re down to four queries: the shortcode queries. Why does WPEC even need to look these up? Well, in order to create URLs for products, WPEC needs to know the base URL, which is set to the page where your productspage shortcode is set. There’s no easy way to get these, so it has to do a LIKE query across all of your pages. Doing this on each page load is a huge strain though (there is a bug filed about this though, so the developers are aware), especially given that we’re not going to be changing this often.

My favourite way to do this, as you may have noticed, is to hardcode it. Unfortunately, there are no filters on this, so you’ll need a custom patch to WPEC to add support for this. Essentially what the patch does is allow the page names to be set previously. I personally think that wp-config.php is the best place for these to live, but it’s your choice on where it is. Here’s what your code should look like:

global $wpsc_page_titles;

$wpsc_page_titles = array(

'products' => 'store',

'checkout' => 'checkout',

'transaction_results' => 'transaction-results',

'userlog' => 'your-account',

);

(The values should be set to the slug for each page respectively.)

Voilà, we’re down to zero queries from WPEC! This should minimise any extra stress on your MySQL server when it’s really not needed.

Sidenote: Some of these inefficiencies can be patched in WPEC, while others can’t be, due to the nature of hardcoding them. For those that can be patched, I’ll be attempting to work with the WPEC team to help them fix it. A quick site benefits everyone. 🙂

Edit: WordPress has __return_zero() built-in, thanks Rarst.

Konstantin Kovshenin recently posted on his blog about creating a WP_Plugin class. He posted an example of a class to fit his thoughts around it on Gist, and from there, discussion has taken place on how such a class would be implemented.

There has been a fair bit of discussion on my fork of Konstantin’s code about this, and I’ve been updating the class with new ideas as we come across them.

However, as is usual with discussion regarding any semi-complicated piece of code, there has been some disagreement on how best to hook methods in. Mike Schinkel is a fan of mapping method names directly to hooks, whereas I much prefer prefixing methods that I want hooked with either action_ or filter_. (We both agree that PHPDoc tags are a good idea though, although Mike also adds a @wp-nohook to ignore any methods.)1 I thought I’d further flesh out why I’m not a fan of mapping the methods directly.

Personally, while I see the merit in naming methods for hooks directly, I hate magic. I hate not knowing when my code is used, and I think one of the biggest strengths of WordPress is that this hardly ever happens. If I want something used, I explicitly declare that through add_action/add_filter.

Don’t get me wrong: I love making things easier for myself. One of my favourite pieces of code ever is one written by Morten Fangel that I use in almost everything I do: _sortArgs(). This piece of code will take an associative array, like array('a' => 'b') and map the variables to parameters to my function. Combined with $_GET and $_POST, it’s an extremely powerful tool. However, _sortArgs isn’t really that magical when it comes down to it. I’m specifying which parameters I want, and everything is explicitly written by me.

I can see the same thing with this plugin class. If I prefix a method with action_ or filter_ (or using PHPDoc tags), I’m explicitly stating that I want this hooked. On the other hand, a method like init is completely implicit. It happens to match a WordPress action, but that could be a coincidence.

As an example of where this would be a problem for me: I often write a method like admin_page for whatever page I’m adding to the admin. If I have things spread across several pages, I’ll factorise the common header bits and footer bits into admin_header and admin_footer. Except with implicit hooking, I’ve accidentally just hooked my footer method into the administration footer. Now, I have to undo that by specifying that I don’t want it hooked.

To hook implicitly requires that I know every action/filter in WordPress to avoid conflicting with them.

Even worse than this is that hooking implicitly breaks forward as well as backward compatibility. Let’s say I add a method called after_post which I call from another class in my plugin, so I need it to be a public method. Everything is going well, until WordPress adds a hook into templates for adding content after a post. Oops, suddenly, my plugin breaks through no fault of my own, and through something that core developers shouldn’t (and wouldn’t) have to worry about.

Hooking implicitly breaks compatibility in every direction, and is too magical. It is absolutely not the way to consume a public API.

Sidenote: A discussion also emerged on how to use priorities. Mike and I both agree (I think) on using PHPDoc, while Thomas Scholz prefers preferred suffixing the method (i.e. action_init_2). My problem with this is that distinguishing between an named init with priority 2 and an action named init_2 is impossible.

Edit: Thomas dropped support for priorities in the method name, which I initially missed. Thanks for the correction.

Edit 2: Updated with a footnote about Mike’s position regarding implicit/explicit hooking.

This morning, I switched the theme on here, Beached, over from using meta fields to WordPress 3.0’s new custom post types. Aside from having to do a manual SQL query to covert the posts, it has worked wonderfully. This also enables me to have different permalinks for links (for example, this post is /92/wp3-custom-post-types/, while a link with the same title would be /link/wp3-custom-post-types/), and in the future, other fun stuff like separate feeds for links and posts, with one combined one. It’s definitely a very powerful feature.

As any good plugin developer knows, WordPress 2.8 introduced a new way to handle the changing of options. The register_setting() function is used in combination with options.php to create an easy way to create option pages for plugin settings. This enables the plugin developer to focus on his plugin, rather than spending a great deal of time creating options pages.

Sounds great, right? Well, sure, until you introduce nonces (which you should).

For most developers, using the update-options nonce, in combination with the page_options POST variable, will suffice, and works fine with their current code. However, the code itself says “this is for back compat and will eventually be removed”. Being good developers, we want to keep up with the latest standards, and make sure our plugins work in future versions of WordPress. Our other option is to set the option_page POST variable. This sounds fine, as we already have unique identifiers for our plugin functions (right?), so we can simply do <input type="hidden" name="option_page" value="rm_plugin_options" />, right?

Wrong. Turns out, you need to do one extra step: whitelisting your options.

Whitelisting your options is what you usually do with page_options, except, that POST variable isn’t used when we use option_page. Instead, we need to whitelist the options in the HTML, via the whitelist_options filter. I could explain the setup of whitelist_options, but you can find that out by simply looking at the source of wp-admin/options.php. Instead, here’s some example code. Enjoy.

function rm_whitelist_options($whitelist) {

// option_page is the key here, values are option names to let through

$whitelist['rm_plugin_options'] = array(

'pixopoint_themeoptions',

);

return $whitelist;

}

add_filter( 'whitelist_options', 'rm_whitelist_options' );

So, finally done? Nope, still have one last thing to do: nonces! This is the most simple part. You must set it to [option_page]-options for options.php to accept it.

Finally, we have it done. Now, good luck with your plugin!